Snow Algae Atlas Project Overview

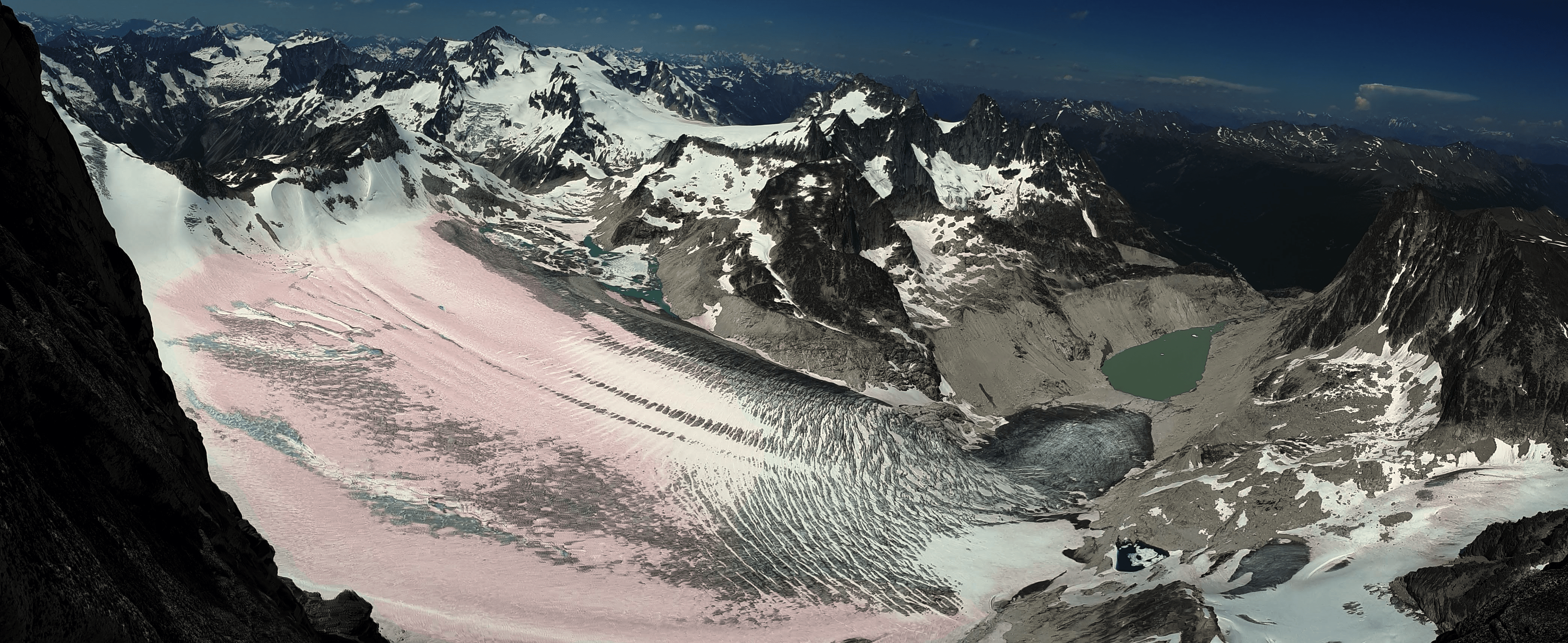

Although we typically think of snow as sterile and lifeless, in summer the snow surface is in fact teeming with life. The melting snow provides liquid water that supports pink blooms of single-celled algae called ‘watermelon snow’, which feed a diverse microbiome of microscopic grazers, parasitic fungi, and symbiotic bacteria. Fascinating in its own right, this microbiome is also important for its role in the broader ecosystem: the algae “eat away” at the snow. The red algae darken the snow surface, melting away pockets of snow like holes in Swiss cheese.

By regulating snow melt, snow algae could play a vital role in mountain ecosystems. The timing and release of snowmelt impacts plant phenology in alpine meadows, and provides water throughout the summer for downstream habitats. Among other things glacial runoff cools the water temperature for salmon, and transports nutrients that fertilize oceanic plankton. Summer snow reservoirs are also an important source of water for human irrigation and drinking water, and early snow meltout can tip the scales towards drought and wildfire. Snow is an excellent reflective surface, so loss of snow cover means more solar energy absorbed by Earth—another vicious feedback loop of global warming.

We still don’t know how widespread or frequent these blooms are, or whether they are increasing with climate change. Here in British Columbia, we see entire glaciers almost completely covered in pink snow. The pink snow tends to occur at middle elevations in the ‘Goldilocks zone’: too low and there is no snow in summer, too high and the snow remains frozen and the algae can’t grow. So looking for pink snow in satellite images seems like a good place to start.

However, other things also cause the snow to appear pink in satellite images: for example mineral dirt, or ash from wildfires. To differentiate real algae from false positives like ash and dust, we used a classification algorithm (called Random Forest) that predicts whether it is algae or something else. The algorithm was trained by visual interpretation of satellite images–admittedly subjective. But, now we can make predictions. And go out in the field and test those predictions.

This summer, hikers and mountaineers can help us ground validate our snow algae satellite map by visiting predicted “Algae” and “Other” locations. Here’s how it works: a few days before your trip, check the web app for any predicted points in your region. In the field, navigate to those points with the Gaia GPS app and classify whether or not the point is predicted correctly.

If you like to spend time in the mountains, please consider signing up to participate in our citizen science project. As a bonus, participants recieve a free 1-year Gaia GPS Premium membership on signup! For more information, please see the step-by-step instructions.

2022 UPDATE: This project is no longer actively recruiting volunteers. If you are still interested in volunteering, please see https://wp.wwu.edu/livingsnowproject/.